Any small business owner will tell you that it isn’t easy being small. You wear many hats, you work crazy hours and you may need to look really hard to find the resources to expand, especially in today’s economy.

Still, a small, flat organizational structure does have its pluses: the power to move quickly, the freedom to take chances, the lack of quarterly earnings pressure and more.

That’s why, despite the beating many restaurants have taken since the global economic crisis, many small operators have mustered the courage and the resources to forge ahead with often ambitious expansion plans. Here’s how they have managed to flourish.

They find great partners.

Jeremy Fitzgerald had a family background in hospitality when he decided to buy a Subway franchise. Still, he never lost sight of his ultimate goal, which was to create a concept of his own and start franchising it. He teamed up with a trusted friend, George Simon, to open Bar 145, a Toledo gastropub promising “burgers, bands and bourbon.” Twenty bourbons, better burgers and live entertainment six nights a week are the signatures. The first location opened in May 2011, a second is due to open late in 2012 in Kent, OH, and three more next year. Fitzgerald envisions a mix of corporate and franchise locations.

The duo’s strengths complement each other: Simon looks after the numbers, and Fitzgerald works on the details of the product. “George did not have any experience in the restaurant business, but as a successful business owner himself, he provided me with financial backing in addition to a profound understanding of the business end of running your own company,” Fitzgerald says.

Neophytes aren’t the only ones who can benefit from strategic partnerships. Lark Creek Restaurant Group’s veterans (including Michael Dellar and Bradley Ogden) have expanded to a portfolio of 12 restaurants centered around the heavily competitive San Francisco Bay area with a little help from their landlords.

Lark Creek has worked out revenue-sharing agreements with property owners that turn out to be a win-win. “They’ve been more than willing to be very generous with tenant improvements that are far above the industry norm,” Dellar says. “That has allowed us to build high-end restaurants with limited capital from us.” Those partnerships sometimes extend beyond tenant improvements, too. Some landlords have agreed to split development costs, then pay Lark Creek to manage the restaurant.

They are nimble.

Tim Spinner and Brian Sirhal, protégés of Jose Garces, opened Cantina Feliz and La Calaca Feliz in and outside of Philadelphia a year apart, and a year later they’re embarking on their third project, a fast casual concept. It’s a pace the two would like to continue.

The lack of a defined infrastructure has helped Spinner and Sirhal shape their concepts and fuel that growth, Sirhal says. “It’s nice to be able to just tweak things at a moment’s notice,” he observes. “We are able to get direct feedback from our managers, servers, bartenders and cooks. And they’re not shy about sharing their opinions if they think something isn’t working.”

James Brennan, who has partnered with Brian Malarkey to open a collection of five hot restaurants (Searsucker, Burlap, Gingham, Gabardine and Herringbone) in San Diego, says the lean structure of Enlightened Hospitality Group allows it to jump on opportunities quickly. Looking to expand into Phoenix, they found a prime location where a restaurant had failed on a Saturday night. “By Tuesday the landlord had 30 offers. One of the advantages we had—beside the fact that the guy had eaten at Searsucker and loved it—is that there was no chain of command to make the decision,” Brennan says.

Acting swiftly and developing more than one project at a time have allowed Enlightened Hospitality to grow from a single location two years ago to five. Brennan expects to add 15 more units—additional locations of the existing brands—over the next five years.

They look for niches to fill.

Arsalun Tafazoli and Nathan Stanton eyed the San Diego restaurant scene and didn’t like what they saw. “Restaurants were defined by bad entertainment, plasma TVs, cheap products—the worst common denominator,” Tafazoli says. “We wanted to take a step back and create places that were conducive to conversation and had a good product.” The two started creating “socially engineered” restaurants, designed to encourage interaction, with a focus on craft beers and cocktails. In the past five years, they’ve opened five unique spots. They’ve stepped up their game with the two latest products, Soda & Swine and Polite Provisions, which will team the Michelin-starred chef Jason McLeod and master mixologist Erick Castro. Jerry and Laura Lasco, with no previous hospitality experience, launched a Houston wine bar and retail store called Max’s Wine Dive to capitalize on the growing popularity of wines. A global wine list and gourmet comfort food served in an urban chic, relaxed atmosphere define the concept, whose slogan is “Fried chicken and Champagne? Why the hell not?!?” Diners can purchase wine on the spot at bargain prices. The concept includes a retail component called the Black Door. Clearly the combination has resonated with the public: The fourth Max’s location opened last July in Dallas.

Jerry and Laura Lasco, with no previous hospitality experience, launched a Houston wine bar and retail store called Max’s Wine Dive to capitalize on the growing popularity of wines. A global wine list and gourmet comfort food served in an urban chic, relaxed atmosphere define the concept, whose slogan is “Fried chicken and Champagne? Why the hell not?!?” Diners can purchase wine on the spot at bargain prices. The concept includes a retail component called the Black Door. Clearly the combination has resonated with the public: The fourth Max’s location opened last July in Dallas.

“Our vision statement is to ‘revolutionize the wine experience,’ and this is a big part of it,” Jerry Lasco says.

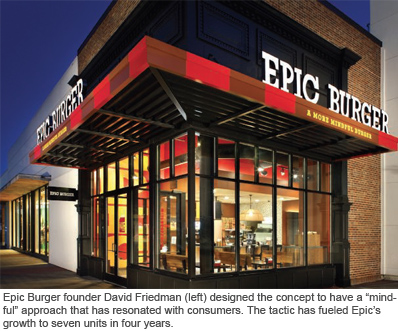

Because it’s so saturated, the challenge of the burger segment is to rise above the noise. Epic Burger’s angle, which has helped it grow to seven units in four years, is to exploit the public’s concerns about sustainability.

Founder David Friedman created a “mindful” experience with Epic through a variety of practices, such as sourcing humanely raised meats that are free of antibiotics, hormones and additives; nitrate-free bacon; preparing trans fat-free fries with sea salt; serving cage-free organic eggs; using plant-based packaging and providing a nutritional fact calculator.

“I think the concept is really relevant to the growing base of consumers looking for something a little more healthy, mindful and environmentally sensitive,” says Scott Norrick, c.e.o. “This allows us to differentiate ourselves in the customer’s mind. It also attracts good people to come to work for us.”

They never lose sight of the bottom line.

Social experiments aside, even Tafazoli acknowledges that nothing happens if the money’s not there. His portfolio of restaurants has been able to expand through cash flow. “We are transparent about the fact that we are a business,” he says. “It’s about finding a happy medium. If we don’t make money, we can’t grow.”

Some owners are more fanatical. “I am amazed at how many people I talk to who don’t know their costs,” says Steve DeFillipo, owner of Davio’s Northern Italian Steakhouse, with locations in four East Coast cities and plans for two more. “I am a nut about the p&l statements. I go through them item-by-item and ask whether we can do things better. There’s no way you can grow unless you’re making money.”

They build a strong internal culture.

“We make sure our first priority is teamwork,” says owner Jeremy Merrin, who has expanded the Havana Central brand to five locations. He likes to see staff members develop friendships, because he believes it fosters loyalty. “You will tend not to want to leave a company if you are working with friends,” he observes. As Havana Central expands to new locations, maintaining that culture gets more difficult. But Merrin makes sure to bring veterans along to help develop the right atmosphere.

Kevin Finn, president of Iron Hill Brewery & Restaurant, says grooming internal talent is a priority for his company, which has nine brewpubs in the Northeast and will open its 10th next year. Servers endure intensive training and testing before they hit the floor to ensure high standards. Managers clock in “so we can make sure they aren’t working too many hours,” Finn says. The promise of a management post is a compelling incentive, and it’s not just talk. The current director of operations started out with Iron Hill as a hostess.

“I’m passionate about creating opportunities for people, helping them grow and experience things,” Finn says.

Brennan calls the internal culture the DNA of Enlightened Hospitality’s units. “We need to make sure from restaurant to restaurant that the g.m.s, managers, hosts and servers understand the DNA. There is literally a blueprint and a book so everybody understands it,” he says.

That goes double for the DJ, since an eclectic mix of tunes that changes throughout the day defines the restaurant. “The hardest part of the whole DNA thing is certainly the music,” Brennan says. “We have a one-strike policy with our DJs. There is no second chance. And we are meticulous in how we police that.”

They choose sites carefully.

“We tend to be a little prudish or elitist” when it comes to site selection, Lark Creek’s Dellar says. The kind of restaurants Lark Creek builds aren’t going to work in a strip mall or in a less-sophisticated market. “It’s really important for us to locate where people understand what we do and understand the difference between good and great.”

Being able to reach two locations with relative ease is important for a small organization like Sirhal and Spinner’s. “It makes it easy for us to move back and forth. We spend a lot of time together at both of the restaurants, but we can divide and conquer when we have to,” Sirhal says. The third restaurant also will be in the city.

They staff up strategically.

At some point, a growing organization needs to bring in help from the outside. That’s what Merrin found out when he had three Havana Central locations open in New York. When Merrin migrated over from the jewelry business, he quickly learned that running restaurants was a bit more complicated than it looked. “I was working crazy hours, not making money and spending my time putting out fires,” he recalls.

Merrin knew he was onto something with the concept, but he wasn’t happy with how it was developing. He found a consultant—Arlene Siegel—who helped him build a team to take his organization to the next level. One of the first hires was an operations expert who helped him hire better managers and look at processes. He is working on his fifth location and is ready to hire a purchasing director now that the volume is there. And he plans to open two to three restaurants a year going forward, “carefully, so that each restaurant stands on its own.”

“It took us a long time, but we finally figured out how to make money and how to run restaurants.”