Just in time for nationwide implementation of mandatory menu labeling law comes word that a direct connection between eating restaurant meals and weight gain doesn’t exist. “The causal link between the consumption of restaurant foods and obesity is minimal at best,” a new study concludes. Too bad the Brazilian judge who made McDonald’s pay $17,500 to a unit manager who ate too much on the job never read this research.

Professors Michael Anderson of the University of California at Berkeley and David Matsa of Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management are the authors of “Are Restaurants Really Supersizing America?” Their study will appear in a forthcoming issue of American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.

Anderson and Matsa say they undertook their research for this reason: “Many policymakers and public health advocates design policies intended to reduce the impact of restaurants on obesity, even while they acknowledge that convincing evidence of such a link has proven to be elusive.” They point to a recent FDA forum designed to come up with solutions to the problem of obesity caused by away-from-home foods in which the organizers quietly noted that “there does not exist a conclusive body of evidence establishing a causal link between the availability or consumption of away-from-home foods and obesity.”

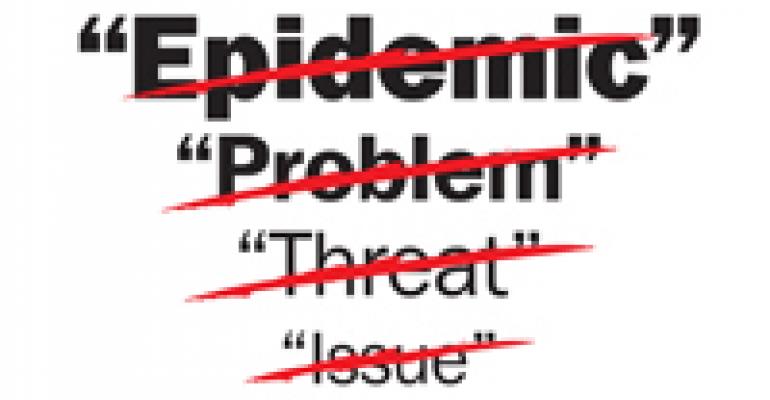

Which is to say, the people who are making restaurants list calories on their menus admit publicly they don’t know if doing so will have any positive effect. That’s one reason the two professors decided “to reexamine the conventional wisdom that restaurants are making America obese.”

We’ll spare you the details of their exhaustive analysis and skip ahead to the conclusions. “Restaurant access and restaurant consumption have no significant effects on obesity.” Period.

The researchers don’t say what does cause obesity, but they do offer an opinion on the efficacy of meddling by government officials and other health advocates. “Regulating specific inputs into health and safety production can be ineffective when optimizing consumers can compensate in other ways. While taxing restaurant meals might cause obese consumers to change where they eat, our results suggest that a tax would be unlikely to affect their underlying tendency to overeat. The same principle would apply to other targeted obesity interventions as well.”

This is music to the ears of restaurant operators, who can only hope that government officials hear it and start focusing their efforts more on the personal responsibility of food consumers than on restaurants.

Judge Joao Filo in Brazil hasn’t gotten the word yet, though. In late October, he heard a case in which a McDonald’s manager claimed that his free lunches at the chain made him fat. The complainant put on 65 pounds during his 12 years of work for McDonald’s. That works out to 5.4 pounds per year, or a weight gain of one-tenth of one pound per week.

Seems like a laughable claim, but the judge took it seriously. He awarded the manager $17,500 in damages.

“We’re disappointed with this preliminary court ruling, as it’s not an accurate representation of our highly regarded work environment and culture,” a McDonald’s spokesperson said. “This case is still a pending matter, and it would be premature to draw conclusions at this time.”

Let’s hope this research from professors Anderson and Matsa causes U.S. officials to stop drawing conclusions that cost restaurants time, trouble and money, without having any demonstrable effect on the serious problem of obesity.